Marginalized Groups are Discriminated Against in the Rental Market, and the Housing Crisis may be Making it Worse

- Megan Earle

- Mar 20

- 6 min read

This work is a summary of a full-length research article published by the Canadian Centre for Housing Rights. Get a complete copy by visiting their website at: LINK.

Research Tools Used for This Project: literature review, archival data, survey data, experimental design, R (programming language), Qualtrics, Prolific, multilevel modeling, structural equation modeling, data visualization

Secure, stable housing is crucial for well-being. But discrimination can make finding stable housing for some groups more difficult. Moreover, the current housing crisis, characterized by high demand for affordable housing coupled with low vacancy rates presumably exacerbates these difficulties faced by marginalized people.

Historically, work on discrimination in the rental market has focused on discrimination that occurs when prospective tenants are looking for a new place to live. This type of pre-tenancy discrimination can take many forms, such as not responding to a prospective tenant’s request to view or rent a unit, steering a prospective tenant away from a particular unit, or otherwise favouring one prospective tenant over another based on some aspect of identity.

Pre-tenancy discrimination research conducted in the United States and Europe suggests that landlords discriminate against prospective tenants based on many aspects of identity, including gender, race, religion, parental status, mental illness, and disability. However, only a few small-scale studies have been conducted in Canada, almost all of which have been focused on major cities.

Moreover, pre-tenancy discrimination only tells us part of the story when it comes to discrimination in the rental market. Even after being housed, marginalized communities often face additional discrimination, or during-tenancy discrimination, at the hands of their landlords. Examples of during-tenancy discrimination include sexual harassment, insults, bending/opposing different rules, and not taking care of needed repairs, among other behaviours. Only a few, mostly qualitative, studies have attempted to understand during-tenancy discrimination in some Canadian communities, making the magnitude and scope of this type of discrimination in Canada difficult to discern.

Therefore, this project consists of two studies. The first study, a discrimination audit of Canada focused on pre-tenancy discrimination, aimed to answer the following questions:

1) To what extent do landlords respond differently to prospective tenants based on renter identity?

2) How do these effects vary as a function of rental unit or regional characteristics?

The second study, a national survey of Canadian renters focused on both pre-tenancy and during-tenancy discrimination, sought to answer the following:

1) To what extent do marginalized groups face pre-tenancy discrimination, or discrimination that creates barriers to accessing housing?

2) To what extent do marginalized groups face during-tenancy discrimination, or discrimination by their landlords after they have moved into a unit?

Study 1: National Discrimination Audit

1178 online rental advertisements across 57 Canadian communities were used for the purpose of this study. Each ad was randomly assigned to receive a message from one of four renter identities that were created for the purpose of this study:

o A White man named Peter McDonald

o A South Asian man named Mohammed Al-Kharat

o An Indigenous woman named Nimkii Kistabish

o And Indigenous woman named Nimkii Kistabish who has a child

Racial identity was indicated via the renter’s name, which was featured in the renter’s email address, in the renter’s message to the landlord, and via the profile picture. The message also featured an intentional typo. Specifically, the message sent to the landlords from fabricated tenants without a child is as follows:

Hi, my name is {renter’s first name} and I’m intersted in this apartment. Can you please confirm the rent price? Is there a security deposit, and how much is it? What information do you need for the rental application? Thank you,

{renter first and last name}

The message from the renter profile with a child was identical, except that this message also indicated that the renter had a one-year-old son.

Each landlord response was coded for indications of differential treatment, including response rate, length of response, whether the response was friendly (e.g., answered the renter’s questions, offered to show the unit), whether the response was unfriendly (e.g., asked more personal questions, requested more pieces of documentation), whether the landlord rejected the tenant, and whether the renter was told a higher rent price than what was listed in the advertisement.

Marginalized Identities Received Fewer Responses, Shorter Responses, and Less Friendly Responses

Across regions, racially marginalized identities (vs. the White identity) were less likely to get a response from a prospective landlord. The White renter received a response 72% of the time while racialized identities received a response 54% to 67% of the time.

Marginalized identities (vs. the White identity) were also more likely to get a shorter response compared to the White identity. Overall, being racialized marginalized was associated with an 18.83% decrease in word count on average.

There was also a significant effect of parental status, where being an Indigenous woman with a child was associated with a 20.33% decrease in response rate, 28.34% decrease in word count, and received 36.44% fewer indicators of a friendly response relative to the Indigenous woman without a child.

Social and Economic Conditions Affect the Likelihood of Discrimination

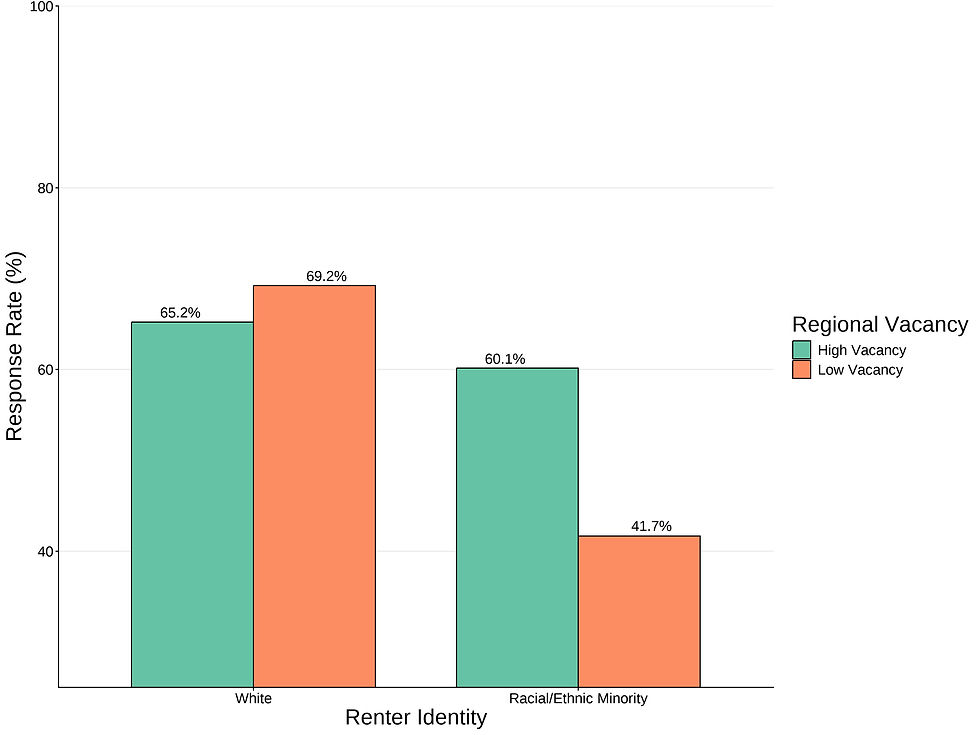

Local social and economic conditions can either exasperate or dampen landlord’s likelihood of discriminating against marginalized groups. For example, racially marginalized identities were especially likely to get shorter responses in areas with lower vacancy rates, compared to the White identity.

High income inequality also exasperated the gap between the White identity and the marginalized identities in friendly responses. In other words, marginalizes identities were especially likely to get a less friendly response than the White identity in areas with higher income inequality.

Marginalized identities (vs. the White identity) also tended to get less friendly responses in areas with higher population density.

There was also an additional effect of parental status, such that the racialized woman with a child was especially likely to get shorter responses relative to the racialized woman without a child in areas with higher average rents.

Overall, these finding indicate the prevalence of race-based pre-tenancy discrimination in Canada. Moreover, these findings indicate that climates characterized by greater competition, more economic inequality, and more scarcity of rental units hurts racially communities more, by exacerbating the discrimination they must face when looking for a rental unit.

Study 2: Survey of Canadian Renters

Surveying Canadian renters about their experiences with discrimination allowed us to broaden the scope of demographic characteristics that can be assessed. In addition to pre-tenancy discrimination, this study also looked at during-tenancy discrimination, or discrimination that tenants face while living in their rental unit. In total, data from 586 Canadian renters were used in this study.

Pre-tenancy Discrimination is Prominent Across Multiple Marginalized Groups

Racial minorities (vs., White people), women (vs. men), newcomers (vs. Canadian citizens), people with lower (vs. higher) income, people living with (vs. without) children, and people with (vs. without) a disability were more likely to experience pre-tenancy discrimination. This most often occurred in the form of the landlord asking the prospective tenant more personal questions, such as questions about visitors, smoking, age, or religion, landlords being more likely to reject the tenant by, for example, refusing to show the unit, landlords placing more monetary barriers, such as asking for more pieces of income/employment related documentation, and landlords being less likely to respond to, the prospective tenant.

During-Tenancy Discrimination Included Landlords Violating Boundaries, Ignoring Maintenance Issues, and Aggression

Racial minorities (vs., White people), newcomers (vs. citizens), lower (vs., higher) income people, single (vs., married) people, and people with (vs. without) a disability were also more likely to experience during-tenancy discrimination. This most often occurred in the form of having boundaries violated, such as a landlord entering a unit without notice, landlords not responding to maintenance issues, landlord aggression, including physical, verbal, or sexual assault, and landlords expecting tenants to rules that different from those applied to other tenants.

What it Means

These findings indicate that marginalized groups continue to face rental housing discrimination in Canada, and that the problem may only be worsened by socioeconomic conditions characterized by low vacancy rates and high income inequality. Moreover, after finding a unit, marginalized groups often face additional discrimination at the hands of their landlords during tenancy. As such, policy and advocacy efforts are needed to confront landlord discrimination on both fronts.

Further Reading

Canadian Centre for Housing Rights (CCHR). (2025). Measuring discrimination in rental housing across Canada. Canadian Centre for Housing Rights. https://housingrightscanada.com/reports/measuring-discrimination-in-rental-housing-across-canada/

Canadian Centre for Housing Rights (CCHR). (2009). “Sorry, it’s rented.” Measuring discrimination in Toronto’s rental market. Canadian Centre for Housing Rights. https://housingrightscanada.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CCHR-Sorry-its-rented-2009.pdf

Canadian Centre for Housing Rights (CCHR). (2022). “Sorry, it’s rented.” Measuring discrimination against newcomers in Toronto’s rental housing market. Canadian Centre for Housing Rights. https://housingrightscanada.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CCHR-Sorry-its-rented-Discrimination-Audit-2022.pdf

McCullough, S., Sylvestre, G., Dudley, M., Vachon, M. (2023). Shut out - Discrimination in the rental housing market: Barriers to tenancy access and maintenance, its impacts, and possible interventions. Institute of Urban Studies, The University of Winnipeg. https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/ius/